Inheritance - Using superJ8 Home « Inheritance - Using super

We finish our investigation of inheritance by looking at accessing members in our superclasses using the super keyword. Ok, we have instance variables and instance methods in our superclasses that we want to access from our subclasses, but how can we access them. We can get to our superclass members using the super keyword. In this lesson we look at how to use the super keyword to access instance variables and methods before looking at superclass overrides and superclass constructors.

Accessing Superclass Members Top

In the last lesson we mentioned the fact that we do not override instance variables in a subclass with the same identifier in the superclass. When we do this it is known as hiding and is not recommended as it can lead to confusing code. But we will show it here along with accessing superclass methods to see how it's done:

package info.java8;

/*

Superclass to illustrate super. access

*/

public class E {

int i = 1;

int j = 1;

public void e() {

System.out.println("Accessing e in class E");

}

}

package info.java8;

/*

Subclass to illustrate super. access

*/

public class F extends E {

int i = 2;

String j = "two";

public void print() {

System.out.println("i in superclass = " + super.i);

System.out.println("i in subclass = " + i);

System.out.println("j in superclass = " + super.j);

System.out.println("j in subclass = " + j);

super.e();

f();

}

public void f() {

System.out.println("Accessing f in class F");

}

}

package info.java8;

/*

Test class to illustrate super. access

*/

public class TestEF {

public static void main(String[] args) {

F f = new F();

f.print();

}

}

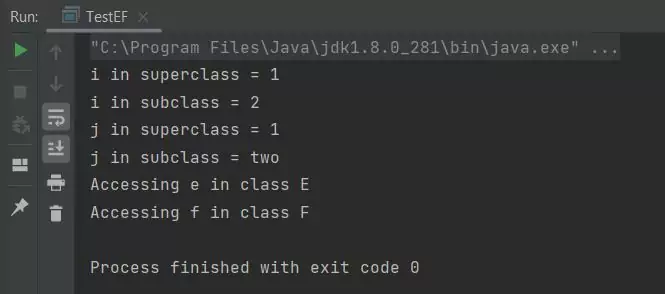

In the above code the instance variables i and j in class F hide the same named in class E. We are actually redefining the j instance variable to a String

object. We use the super keyword to access the superclass instance variables and methods and print everything off.

TestEF class.The above screenshot shows the output of running our TestEF test class after compiling classes E and F.

Accessing Superclass Overrides Top

Wouldn't it be nice if we only had to partly implement code in the overridden methods of our subclasses and left the more generic code in the superclass. This is the whole point of subclassing after all; to avoid

duplication and enhance reusability. We can have partial implementations we can access and use, we do this using the super keyword:

package info.java8;

/*

Superclass to illustrate super. overrides

*/

public class G {

public void a() {

System.out.println("All the generic code from the superclass");

}

}

package info.java8;

/*

Subclass to illustrate super. overrides

*/

public class H extends G {

public void a() {

super.a();

System.out.println("All the specific code for the subclass");

}

}

package info.java8;

/*

Test class to illustrate super. overrides

*/

public class TestGH {

public static void main(String[] args) {

H h = new H();

h.a();

}

}

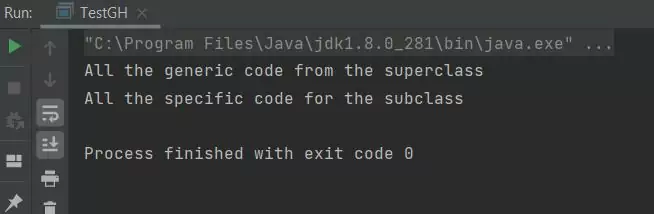

It is very easy to use the superclass to implement generic code , we just need to put in a call to the superclass method from our subclass override method using super and it's done. The actual

syntax used is exactly the same as for any other member but goes in the override method. Just remember to put it before any subclass code in the override so you don't overwrite any subclass specific stuff.

TestGH class.The above screenshot shows the output of running our TestGH test class after compiling classes G and H.

Superclass Constructors Top

And what about constructors, what happens with them when we use inheritance?. We know the compiler creates a no-args constructor for us if we don't supply one, is this the same for

inheritance? Before we answer these questions, we need to first look back to the first Java class we wrote on the site, the Hello.java class:

package info.java8;

public class Hello {

public static void main (String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}

Unbeknown to us, this simple program was implicitly extended by the compiler, in fact every program we write has an implicit superclass called Object. How can this be though,

how can our Garbage class extend Truck and Object, we know we can only extend one class. Well the compiler just travels up the inheritance tree and tries to

extend our Truck class. The Truck class extends the Vehicle class so the compiler travels up the tree again. The Vehicle class extends nothing so the compiler implicitly

extends the Vehicle class with Object. What this means for us is that we get to inherit the methods of Object which we will talk

about in the Object Superclass lesson later in this section. For now, we just need to know that we inherit from Object at the top of our hierarchy.

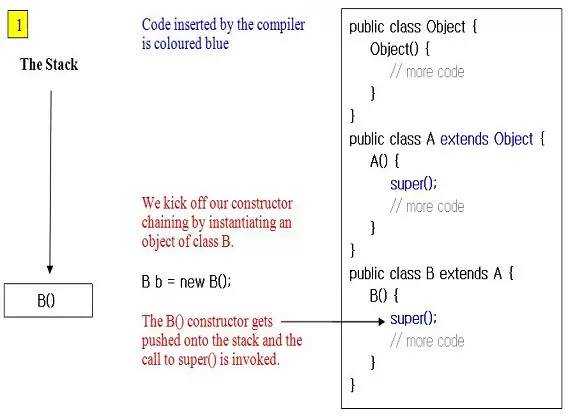

Getting back to our original question about constructors and inheritance, if we haven't supplied a constructor, then the compiler inserts a no-args constructor in each of our subclasses for us, the same as

normal. Not only that the compiler also adds super() as the first statement within our constructors. What does the call to super() do? It calls the constructor in the superclass and if this has

a superclass, you can see where this is going, it also calls super(). Even abstract superclasses have constructors, we just can't see or use them. This continues all the way up the

inheritance tree until we reach Object and is known as constructor chaining. But why does the compiler do this I hear you ask! Well if we think about it, our subclass

might need state from any of its superclasses instance variables or need that state to use superclass methods and it gets them from calling super(). Even if the instance variables have

private access our subclass still needs the methods that use them. The calls to super() just get added to the stack until we hit Object and then are

removed from the stack as they get processed. It's time for a slideshow to explain constructor chaining, just press the buttons to step through it.

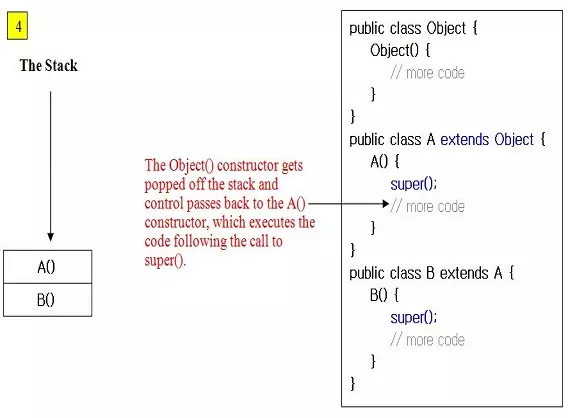

As you can see calling new on an object involves a lot of work for the JVM behind the scenes. The point to get from the slideshow is that even though the B class gets pushed onto the stack

first the code after the implicit call to super() is actually the last to be executed. The Object code will always execute first and then down the constructor chain

until we get to the actual objects code we instantiated. This makes sense, because each subclass might have dependencies on the object state of the superclass above it. But what about constructors

with arguments, doesn't the compiler always insert a call to super() for us? Well yes it does, if we don't supply a call to super() ourselves. If fact we have complete control over how our objects

are constructed because we have the option of supplying arguments when we code our own calls to super(). And if we do so, then the constructor in the superclass matching the signature of our call to

super() is the one that gets invoked. The following code shows how we invoke a superclass constructor using arguments:

package info.java8;

/*

Superclass to illustrate invoking super()

*/

public class I {

private int i;

I(int i) {

this.i = i;

System.out.println("In I() constructor");

}

}

package info.java8;

/*

Subclass to illustrate invoking super()

*/

public class J extends I {

private int j;

J(int i, int j) {

super(i);

this.j = j;

System.out.println("Back in J() constructor");

}

}

package info.java8;

/*

Test class to illustrate invoking super()

*/

public class TestIJ {

public static void main(String[] args) {

J j = new J(10, 20);

}

}

We use the super(i) call as the first statement in class J to invoke this constructor in class I. This fills out part of the J() constructor which does the rest on returning.

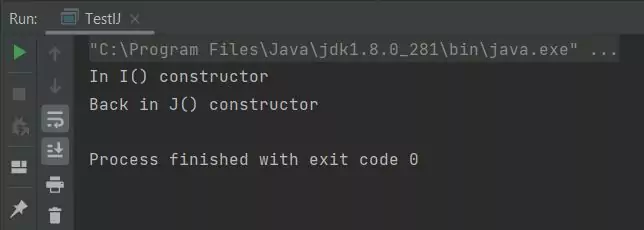

TestIJ class.The above screenshot shows the output of running our TestIJ test class after compiling classes I and J.

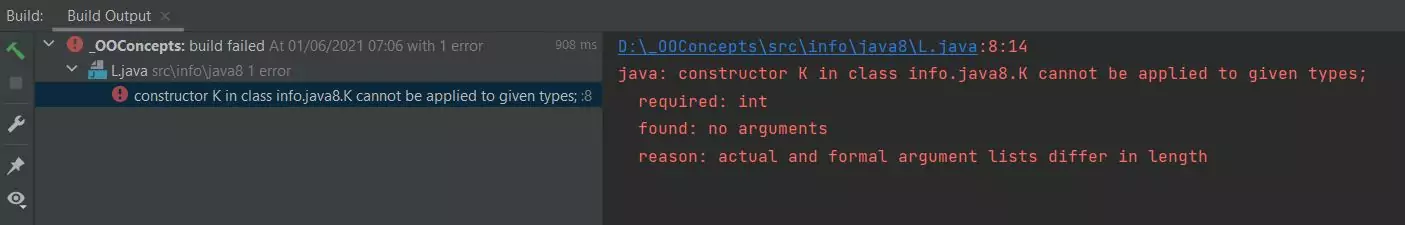

Before we leave super comstructors behind there is one more thing you need to be aware of. Because we have made a constructor in the superclass I there is no longer a default constructor supplied by the

compiler. Why should this matter to us? Well if we create another subclass of class I and don't explicitly call the super(arg) constructor the compiler puts in an implicit call to

super() for us. This results in a compiler error as there isn't a no-args constructor in class I. Time to see this in action:

package info.java8;

/*

Superclass to illustrate implicit super() when there is no no-args constructor

*/

public class K {

private int k;

K(int k) {

this.k = k;

System.out.println("In K() constructor");

}

}

package info.java8;

/*

Subclass to illustrate implicit super() when there is no no-args constructor

*/

public class L extends K {

private int l;

L(int l) {

this.l = l;

System.out.println("Back in L() constructor");

}

}

L class.The above screenshot shows the result of compiling classes K and L. We got a compiler error because the implicit call to super() supplied by the compiler didn't find a match. So the thing here is to either put a no-args constructor in the superclass, or do an explicit call to super() in the subclass.

Now we know about implicit/explicit calls to super() it should be apparent that if you mark a superclass constructor with the private access modifier, any subclass that tries to extend it will fail with a compiler error when trying to access the superclass constructor with super(), either implicitly or explicitly. This of course defeats the whole point of inheritance, but is just something to be noted.

See the Constructors lesson in the Objects & Classes section for more information on constructing our objects.

Inheritance Checklist Top

- We create an inheritance hierarchy using the

extendskeyword wherein the subclass broadens the superclass. - The subclass inherits the members of the superclass, assuming the access modifiers permit inheritance.

- We can use the

IS-Atest to verify that the inheritance hierarchy is valid and this test works from the subclass up the inheritance chain of superclasses, but not the other way around. - We can override the inherited method members as long as we adhere to the following rules:

- A method override must have exacly the same arguments as the superclass method with the same method name or you end up with an overloaded method.

- A method override must have the same return type (or co-variant thereof) as the superclass method with the same method name.

- When we override a method, the overriding method can't be less accessible, but can be more accessible.

- You cannot override a method marked with the

finalmodifier. - You cannot override a method marked with the

privateaccess modifier. Even if you have a method in the subclass with the same method name and arguments as a private method in the superclass it knows nothing of that method as it can't see it and is just a normal non-overriding method - You cannot override a method marked with the

staticmodifier as overridden methods pertain to instance methods and not the class. In fact if you use the same static method and parameters in a subclass as a static method in a superclass this is known as method hiding and is discussed in Static Overrides?.

- We can access members from the superclass above the subclass using

super.memberName. - We can use

super()to invoke a superclass constructor and if we don't supply this explicitly, then the compiler inserts a no-argssuper()for us as the first statement in the constructor if we haven't used thethis()keyword. - When explicitly coding

super()we can supply arguments to invoke a constructor in the superclass matching the signature of our call. - When explicitly coding

super()it must be the first statement within the constructor or we get a compiler error. This means we can't usesuper()andthis()together.

There are other rules regarding exceptions declarations when using overrides and these are discussed in the Exceptions section when we look at Overridden Methods & Exceptions.

Related Quiz

OO Concepts Quiz 7 - Inheritance - Using super

Lesson 7 Complete

In this lesson we continued our investigation of inheritance by looking at accessing instance variables, methods and constructors in our superclasses using the super keyword.

What's Next?

We continue our investigation of OO concepts by looking at abstraction.